Changing lives and transforming organizations through leadership, education, and consultation

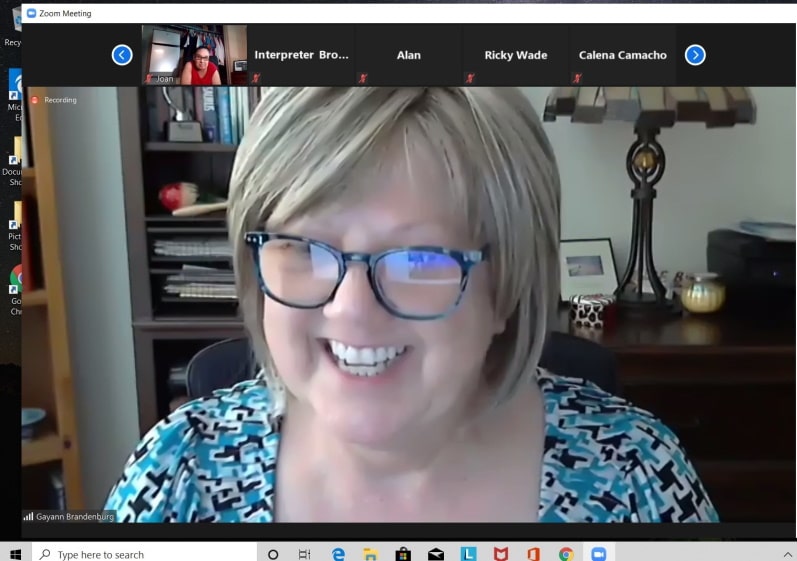

Gayann Brandenburg says creating access to buildings, events and transportation can help businesses by including people with physical and intellectual disabilities.

By Eliza Marie Somers

If COVID-19 has taught us one thing it is: To be part of a community, you must have access to that community. That community can be your “tribe.” Community can also be a physical place, such as a library, a gym, museum or a church, or, as we’ve learned in 2020, a digital or virtual place. And while we all are coping with the limited access because of the pandemic this is something people with a disability experience on a daily basis.

“It’s all about equality and civil rights,” said Gayann Brandenburg at the Community Counts! Access to Community Services seminar for people with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (I/DD). The series, created by CTAT, LLC, in conjunction with the City and County of Denver, encourages inclusion for people with I/DD.

“There’s a lot of legislation out there that says we have rights,” said Brandenburg, a founding member of CTAT.

The Americans with Disability Act (ADA) was signed into law in July 1990 and prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public. But barriers still remain for people with physical and mental disabilities.

It’s not only physical barriers Brandenburg explained, it is also access to transportation, employment, housing, communication, and quality medical and dental care that affects people with I/DD and physical disabilities. More and more, it is also access to digital spaces and communities. This access is contingent on accessible websites, shopping carts, virtual platforms such as Zoom, etc. For more information visit: ADA Best Practices Tool Kit for State and Local Governments at link https://www.essentialaccessibility.com/blog/ada-guidelines

“It’s how can I get on the bus? How can I have access to shopping? Are there curb cuts or a ramp? Do they allow service animals?” These are some of the questions Brandenburg said are paramount to someone with a disability.

And don’t forget healthcare. “A lot of people with disabilities are on Medicaid, and a lot of providers don’t take Medicaid because it doesn’t pay well,” Brandenburg said. “There are long wait-lists to see doctors. And there is a higher mortality rate for people with disabilities.”

In 1978, Denver became the epicenter for people with disabilities when a group of activists known as the Gang of 19 stopped traffic for two days at Broadway and Colfax by lying in the street to protest inaccessible public buses. The protest resulted in Denver becoming the first city to have an accessible public transportation system. But the system is not perfect, as members of the Access To Community Services panel described unreasonable wait times for Access-A-Ride, the transportation arm of RTD for people with disabilities, and the solutions they use to cope with the system.

Chris Patton relies on caregivers to take him out into the community.

“Access-A-Ride is not very reliable,” said Chris Patton, who is an individual with autism. He uses a device to communicate and relies on caregivers to take him shopping or to the recreation center. “If it wasn’t for my caregivers, I wouldn’t go anywhere.”

“Sometimes Access-A-Ride is on time, and other times I just sit and wait,” said Dennis Carbrey, who has a visual impairment. Luckily for Carbrey his boss at Taco Bell understands. “He is very supportive and doesn’t give up on me,” Carbrey said.

“It’s hit or miss,” Jocelyn Roy said of Access-A-Ride. She now relies on Lyft or Uber to take her to her job at Access Gallery, which helps her pay for fares.

Dennis Carbrey, who uses Access-A-Ride, says he is grateful for his boss at Taco Bell because of his understanding of the public transportation’s unreliability.

Brandenburg also noted public transportation in Greeley ends at 7 p.m., making it nearly impossible to attend evening events or to work late if someone relies on public transportation.

Many employers don’t realize people with I/DD want to work, so they tend not to cater to this available workforce. “It’s important to have discussions to come to reasonable solutions, and most of those solutions cost less than $100,” said Brandenburg, who is an employment specialist with North Range Behavioral Health and assists job seekers to find and keep employment.

She described a situation in which a young man with I/DD and PTSD had trouble taking orders from male supervisors. Once it was communicated to the company, the employer switched his supervisor to a woman, and the young man flourished and worked there for many years.

“When there is a cooperative mindset there are seldom issues that cannot be resolved,” Brandenburg said.

Employers should also consider accommodations that not only help their employees but their customers, such as clearing aisles to make them wider, dimming lights and reducing noise levels for people with light and sound sensitivities, and making sure doors and ramps are accessible to people with disabilities.

Roy uses earplugs when she attends church because the music is too loud. She also stays away from restaurants and businesses if they do not have automatic doors or if the incline on the ramps are too steep.

“Sometimes in building the ramps are too long, so I just stay away,” Jocelyn said. “Maybe they can make the ramps shorter. If the buildings just have stairs, and I don’t have my cane, I’m screwed.”

Large signage or signs in Braille are an easy way to make a building more accessible.

“If I know the place, I know I can make it fine,” said Carbrey, who has a visual impairment. “If it’s unfamiliar I might go to the wrong building.”

Another way to help people with I/DD is changing the signs for the restrooms from the cute hens vs. roosters or cowgirls vs. cowboys to the boring men vs. women, or just adding those words under the whimsical signs.

Joan Ulibarri said the “welcome” is just as important as getting into the business. That “welcome” can be as simple as a saying hello and asking someone with a disability if they need help, instead of ignoring someone who is different.

“Be nice, be welcoming,” Joan said.

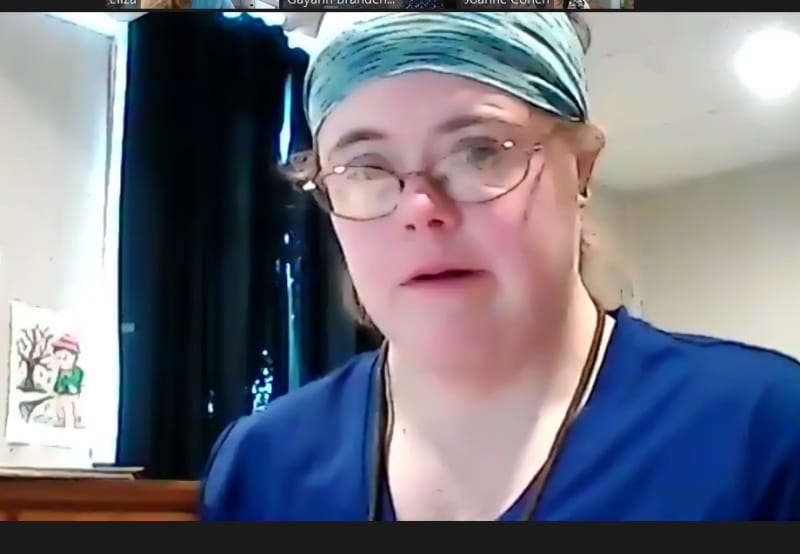

Rachel Kurth says it hurt when people stare and ignore her.

Rachel Kurth, an individual with Down syndrome, said people look at her differently and stare, and sometimes call her names when she goes places.

“Some people don’t like me because I’m different, and call me a retard,” she said.

“I don’t like that. It’s hurtful and painful.”

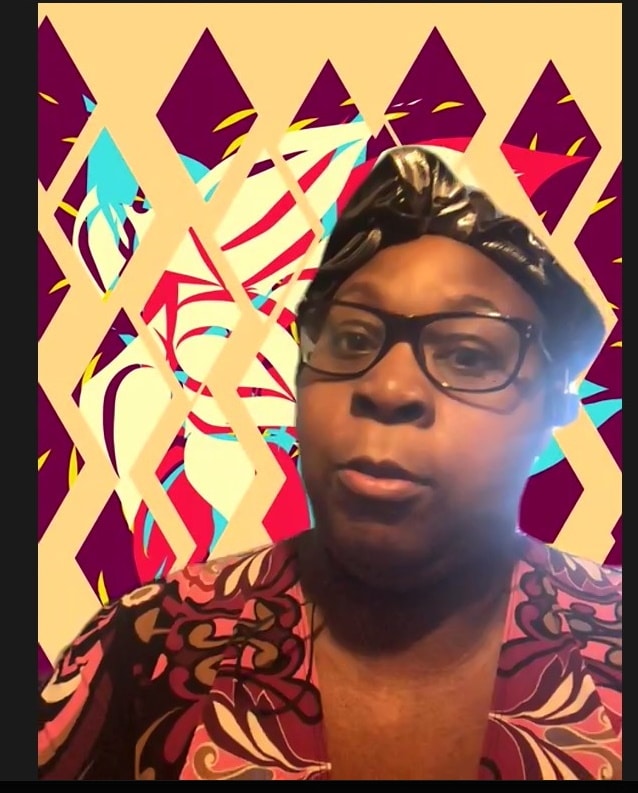

“Ask us if we need help or let us ask for help. And try not to hover over us,” Roy said. “Treat us with respect. A mental disability is invisible, where a physical one is more obvious. Don’t judge us. Just talk to people and get to know them.”

One common thread to gaining access to community is having an advocate.

“My counselor helps me out,” Roy said. “She is my voice. Without her I would not have a voice.”

Jocelyn Roy, who relies on her counselor to be her advocate, says treating all people with respect is a way to make your business accessible.

Ulibarri relies on her family, and said she stays silent if her family is not around to help her.

By breaking down physical barriers and enhancing communication, employers, churches, nonprofits and businesses can be more inclusive to people with disabilities.

“It’s about making people aware,” Carbrey said.

Tips for accommodations:

CTAT, LLC

6732 West Coal Mine Avenue, Suite 227

Littleton, CO 80123

© 2025 CTAT, LLC